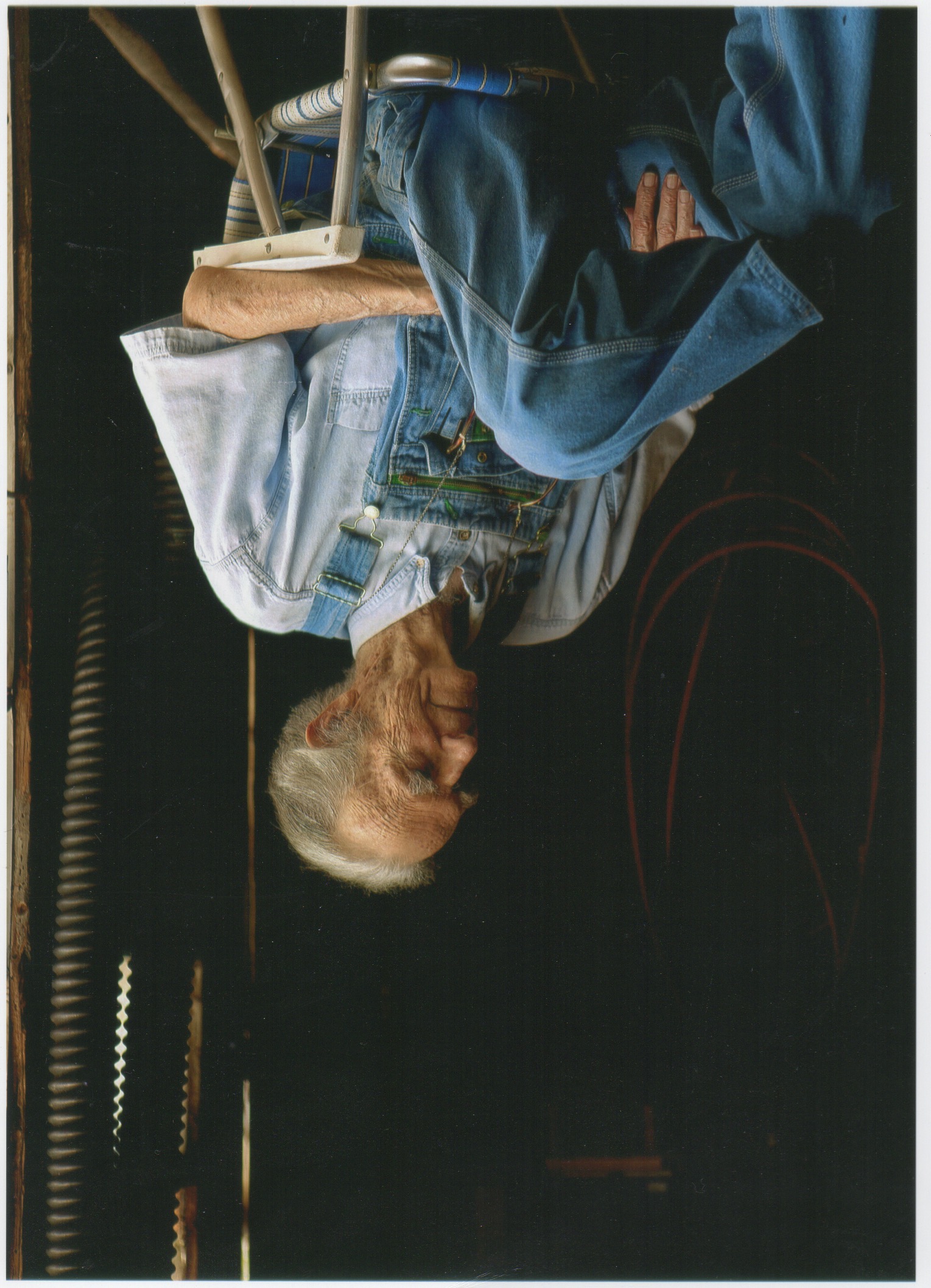

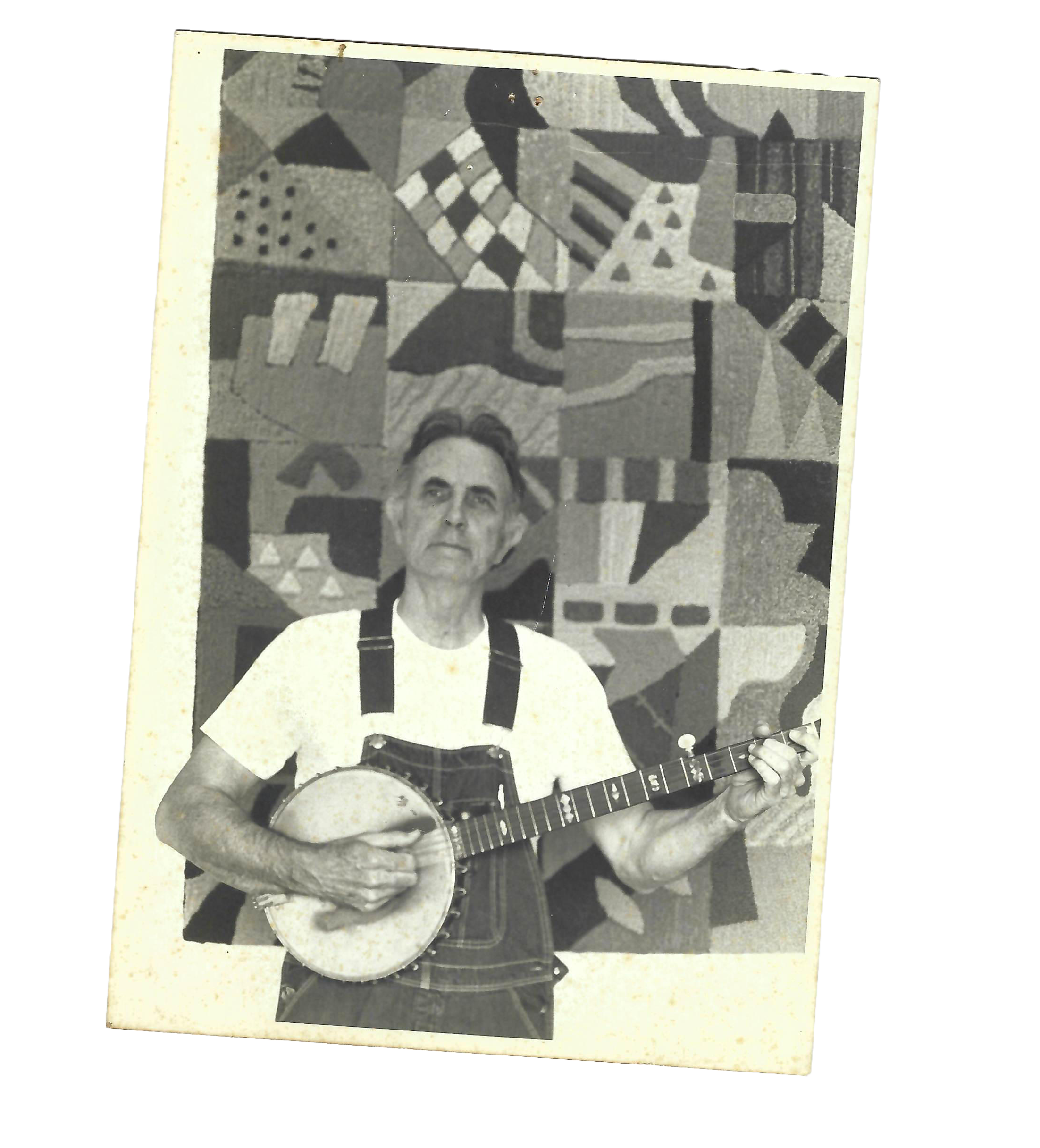

JACK HASTINGS (ESTATE)

Born to a Missouri dredge boat captain, Hastings’ unmoored upbringing swept him along untamed rivers and wild estuaries across the eastern half of the US. He attended upwards of a dozen different schools before finally graduating from Morgan Prep in Petersburg, Tennessee. Shortly after, Hastings volunteered for the US Army Air Corps, serving as a pilot in WWII. Upon his return, he enrolled at LSU. During his time there, he assisted muralist Conrad Albrizio on several large projects, including a mural in the Union Passenger Terminal in New Orleans. In the early 1950’s, Hastings studied at the Escuela de Pintura y Escultura in Mexico City, where he worked under the auspices of legendary muralist Diego Rivera.

Hastings met his lifelong partner, Arlyn Ende, shortly after his return to New Orleans from Mexico. They immediately recognized kindred spirits in one another, falling headlong into a lifetime of collaboration. The first of these creative partnerships was New Orleans’ original contemporary art gallery, Orleans Gallery, cooperatively founded in 1956 in alliance with 10 other local artists.

Together, Arlyn & Jack migrated northeast–to New York City by way of Italy, then Boston and Block Island, RI–before trekking 2,400 miles west again to Tucson. Once settled in the desert, they would regularly return to Block Island as respite from the scorching summer heat.

This period of constant movement, drastically varied climate, and diversity of landscape fostered an artistic flourishing. Jack churned out paintings and sculptures of manifold styles and techniques. By 1960, he had begun to exhibit his sculptures and paintings in New York City. Arlyn served as assistant to the Director of Urban Design during their stint in Boston. She began her own clothing line, dubbed FOGEATER in homage to Block Island’s hazy coastal shrouds. Their artistic engagement with Arizona’s arid habitat culminated in a collaborative effort on what the couple termed “living sculpture” –a diversity of cacti in sculptural vessels made of poured concrete. The works were fabricated in Tucson for an exhibition at George Jensen’s seminal Manhattan gallery. The show quickly sold out.

In 1972, they moved again––this time to Bradyville, Tennessee––intent on learning to farm. Arlyn recounted running “into some hippies on the courthouse in Woodbury” who told them about “a farm for sale near their commune,” (both of which were long gone by the following decade). They purchased their new homestead using the profits from the sale of their Tucson house, plus a final $1,500 which Arlyn made in a lump sum as a cook on a river barge. Her erudite journals provide an incisive window into this experience as a time of reflection and self-definition. In its pages, she ponders gender relations, the nature of labor, and possibilities for collective social and political formations. These reflections are interspersed with weekly menus and recipes, character sketches, poems, and revelatory passages on mysticism––a testament to the radical democracy of Ende’s holistic aesthetic identity.

Jack and Arlyn settled into a symbiosis with the land, a steady rhythm of farm life and making art. The artists raised chickens, entered in annual craft fairs, planted and harvested potatoes, created public sculpture, and worked in tandem with architects on commissions. Any boundary between art and life quickly eroded; the artists plumbed the aesthetic depths of goat herding, saw pure possibility in the blank canvas of an untilled field, and cherished the sacred communion of local artisans and craft-makers.

The couple’s playful color palette and kaleidoscopic geometry manifested in a yin-yang of complementary and opposite mediums: Jack favoring the cold precision of concrete and metal, Arlyn delving into the warmth of textiles and rug hooking. Both collaborated on a number of highly-designed environments with renowned architect Robinson Neil Bass. Jack created large mobiles for commissions, as well as giant concrete landscape installations like the EnviroGarden, featured in Knoxville’s World’s Fair in 1982. Homage to Calder, arguably his masterwork, was installed in the iconic Tennessee Valley Authority building in Chattanooga. The vibrant kinetic sculpture spanned nearly 5 stories in the building's atrium.

Jack and Arlyn settled into a symbiosis with the land, a steady rhythm of farm life and making art. The artists raised chickens, entered in annual craft fairs, planted and harvested potatoes, created public sculpture, and worked in tandem with architects on commissions. Any boundary between art and life quickly eroded; the artists plumbed the aesthetic depths of goat herding, saw pure possibility in the blank canvas of an untilled field, and cherished the sacred communion of local artisans and craft-makers.

The couple’s playful color palette and kaleidoscopic geometry manifested in a yin-yang of complementary and opposite mediums: Jack favoring the cold precision of concrete and metal, Arlyn delving into the warmth of textiles and rug hooking. Both collaborated on a number of highly-designed environments with renowned architect Robinson Neil Bass. Jack created large mobiles for commissions, as well as giant concrete landscape installations like the EnviroGarden, featured in Knoxville’s World’s Fair in 1982. Homage to Calder, arguably his masterwork, was installed in the iconic Tennessee Valley Authority building in Chattanooga. The vibrant kinetic sculpture spanned nearly 5 stories in the building's atrium.

In 1994, Arlyn and Jack moved again, this time to Sewanee, Tennessee. Beginning nearly from scratch in a wooded thicket tucked away amongst the hills, they built their own home and studio. Situated in their new homestead–aptly named Deepwoods–Jack and Arlyn put down roots, their creative spirits quickly embraced by the community. Each continued their own practice; Jack publishing a book of poems (titled The Illuminated History of Darkness) in 2000, Arlyn’s hooked rugs remaining in high demand. Though their work had always been inextricably intertwined, it wasn’t until 2004 that they had their first joint exhibition at Saint Andrews-Sewanee gallery. Together, they became a beloved mainstay of Sewanee’s artistic community, where Arlyn helped to curate and direct the University’s gallery. In 2012, they collaborated on an exhibition at Tinney Contemporary in Nashville, titled “The Essence of Our Ticking.” Shortly after, Arlyn was inducted into the Tennessee State Museum’s Costume and Textile Institute.

Jack passed away the following year in 2013. Arlyn continued to live and work at Deepwoods until her passing in 2022. The Essence of Their Ticking, a retrospective on the lives and works of Arlyn and Jack, will be held at Tinney Contemporary in December of 2022. The work in this exhibit is a lasting monument to the brilliance of Jack and Arlyn; a snapshot into the creative minds of two artists whose spirit touched so many. In honor of the consecrated space they carved out, Deepwoods Studio will be preserved as an artist’s retreat in affiliation with Tinney Contemporary.

![]()

Jack passed away the following year in 2013. Arlyn continued to live and work at Deepwoods until her passing in 2022. The Essence of Their Ticking, a retrospective on the lives and works of Arlyn and Jack, will be held at Tinney Contemporary in December of 2022. The work in this exhibit is a lasting monument to the brilliance of Jack and Arlyn; a snapshot into the creative minds of two artists whose spirit touched so many. In honor of the consecrated space they carved out, Deepwoods Studio will be preserved as an artist’s retreat in affiliation with Tinney Contemporary.

︎︎︎ For all inquiries please contact susan@tinneycontemporary.com

Exhibitions

Two-person retrospective, The Essence of Their Ticking, 2022

Solo exhibition, Retrospective, 2013

Two-person exhibition, The Essence of Our Ticking, 2012